Last year, my baseline was 47 seconds. My final time ended up as 5:12. Yay me.

This year, my baseline is 25 seconds. I suck. I guess that leaves room for improvement?

Last year, my baseline was 47 seconds. My final time ended up as 5:12. Yay me.

This year, my baseline is 25 seconds. I suck. I guess that leaves room for improvement?

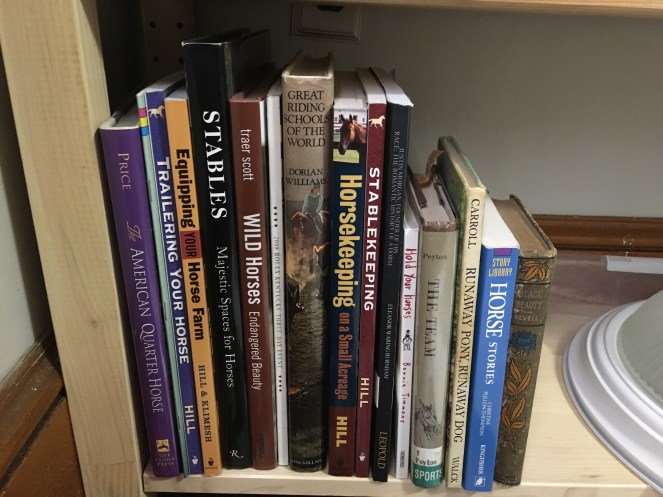

I have…a lot of horse books. Way too many to lay them all out neatly like you guys have. I actually took some down from the shelf to lay them out and then thought about how everything in my house is a disastrous mess and I’d have to spend 20 minutes putting them all back, so. I did not do that.

Here, have pictures of the shelves themselves. My collection is heavier on fiction than on nonfiction, and what nonfiction there is tends toward the memoir & history type than the how-to. I also have another ~20 or so on my Kindle.

Of note: the Cherry Hill books. I love them. Also that lovely old edition of Black Beauty.

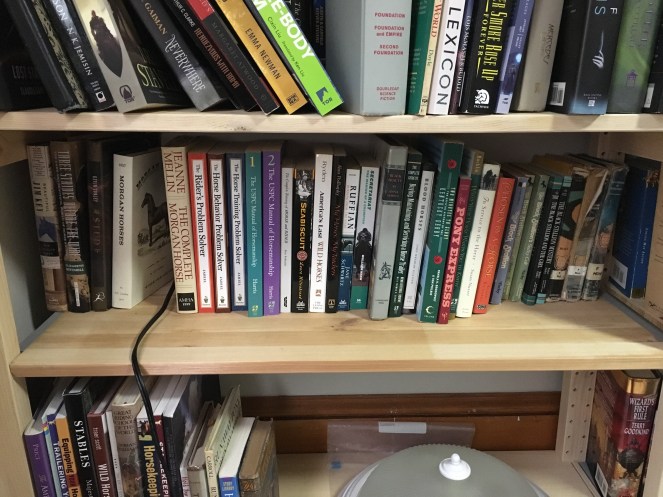

The whole collection, plus the new light that I will install in the library when I have five minutes to spare. Mainly sharing for that top shelf, outer layer. Thoroughbred series, Marguerite Henry, a couple of assorted books, including The Blue Sword, Everyday Friends, and Banner Year, which are all pretty close to perfect hrose books.

Top shelf, back layer. Of note, the USPC books and Jessica Jahiel’s books, as well as my childhood copy of Black Beauty, a few Black Stallion books, and the three on the far right – 1950s horse books written for boys that I loved as a kid. I should write about them someday.

There are at least 5-10 I can think of that aren’t on these shelves, too. I need to do a thorough reorganizing of my books (I have probably ~30 in a stack by my bed alone) but the thought makes me want to go take a nap instead.

In short, I read a LOT.

Book Review: Training Strategies for Dressage Riders from Poor Woman Showing

I like the idea of this book and the positive review it got.

Shaping Energy from Zen and the Art of Baby Horse Management

I had a trainer who was very into the idea of energy use (and chakras!) while riding and I kind of hated it then, but this blog post makes a lot of sense.

Speedhumps: a baby horse story from Dotstream

I love baby horses. This was a well-told story about a training problem & solution.

Eugene’s Eventful Acres – Cross Country from DIY Horse Ownership

I love Eugene, and any post with tons of photos of him jumping gets a +1 from me. It’s also an all-around good show recap.

Millbrook Madness from Breeches and Boat Shoes

*swoon*

Levels of Pressure from A Enter Spooking

A+ for thoughtful, useful dressage content

Use This Easy Test to See if Your Knees Are Inhibiting Your Horse’s Forward Movement from Trafalgar Square Books

I…am not sure this is an easy test, but it is an intriguing one.

The Beauty of Big, Huge, Awkward Mistakes from Eventing Nation

Andrea is the actual BEST, and this is a terrific article.

Countdown to Congress, and the Impending Departure from Diary of an Overanxious Horse Owner

Quarter Horse showing is a world I know absolutely nothing about, so I found this fascinating.

[George] said with attempted lightness, “No need to work over Symbol, heh, Jimmy? He’ll stir up enough wind to wipe him clean.”

Jimmy Creech looked sullenly into George’s grinning, tobacco-stained mouth. “Sure,” he said. “Let’s get the stuff on him now.”

Fuuuuuuck you, Jimmy.

Those are our three main characters; I’ll introduce others later.

The primary conflict in this book is the evolution of the sport of harness racing. Jimmy wants to keep it a small-time sport, with daytime races at local county fairs. The sport at large is moving toward dedicated tracks with evening races under the lights. That’s an interesting narrative, right? There’s a lot to be mined there. The thing that kills me is that Walter Farley gets it. His descriptions of the world of harness racing are as good as – or even better than – anything in the flat racing books. But the entire narrative is presented as one of Good versus Evil, through the lens of Jimmy Creech’s bitterness and anger.

George has some mild opinions on the changes, and Tom has no actual character (other than being a generally easygoing kid and having a natural feel for “the reins”) so the conflict is driven entirely by Jimmy. Jimmy is so upset about the way things are going that he works himself into a bleeding ulcer that has to have surgery. He eats like crap. He has temper tantrums. He screams at the people around him. He sees anyone who has anything to do with the night tracks as a “traitor” and not in the haha-teasing way, in the “you and your kin are dead to me unto the seventh generation” kind of way. He hates drivers at the big tracks so much that he crashes his cart into one of them and gets into a fistfight on the training track with another. Everyone is so afraid of his temper that they tiptoe around him, hide things from him, cater to his every whim, and yes-sir his every statement. Jimmy checks every single damn box on the abusive relationship list.

Jimmy was as highly strung as any colt and his emotions would vary from day to day and from hour to hour.

That’s just the kind of guy I want training horses and/or to be my friend, amirite?

The book has three main chunks: first, the colt’s birth and early life. Second, the colt’s training. Third, the colt’s racing. The colt, by the way, is a blood bay (hence the title) named Bonfire and despite being half-Arabian, half-Standardbred, he is the fastest harness racing horse EVAH. Because of the Black. Or something. Whatever, Bonfire has literally zero personality. After the Black and Satan, he is a big blob of nothing on four legs. He’s easy to train. He wins races. He’s awfully pretty. The end.

Among Jimmy’s more questionable decisions in the book is the decision to send Volo Queen, pregnant with the colt, with Tom for the summer to his aunt and uncle’s house. Tom displays creditable anxiety about this decision, tries to get a vet on-call, and in general takes this responsibility far more seriously than any adults in the book. What do you mean, sending a pregnant mare several hours away to live with a high schooler with zero horse experience is a great plan? On top of everything, Tom is charged with starting the colt – teaching him to be handled, led, etc. Somehow this turns out fine, though damned if I know how. (There are a few screw-ups along the way, but nothing Tom can’t overcome with the power of lurrrrrrve.)

And Tom, I’ve got full confidence in you. Use your own judgment if anything comes up. You’ve got a good head and, most important, the right feeling for horses, and that always pays off in the end.

NO. NO IT DOES NOT, JIMMY.

The training is ok? I don’t know. The horse gets trained. The whole middle bridge displays the fundamental flaw of this book. The training is actually suuuuuuper interesting. Jimmy clearly knows his stuff. I loved learning about harness racing from the ground up. (I have a soft spot a mile wide for harness racing, because all my earliest experiences with horse racing was at Scarborough Downs.)

But the whole middle bit is taken over by Jimmy’s illness (he spends the whole book in denial that he has an ulcer until it ruptures; I’m pretty sure it’s a long game for maximum attention) and by the burgeoning conflict with the night tracks. Two other horses that float in and out of the story are racing at fairs and night tracks, and they’re set up to be Bonfire’s big rivals, but they’re not, really. But the middle bridge means it’s time to talk about the best damn character in the whole book, and a top 5 for the entire Black Stallion series.

Miss Elsie. Miss Elsie is living the dream, you guys. She never married, and inherited her father’s fortune when he died. She spends that money to maintain the training track, breed her own horses, and train all her own horses. She gives exactly zero shits about what anyone thinks of her. She is friendly, but laser-focused on her horses. She is compassionate but doesn’t indulge anyone. She is in and out of the story and is absolutely perfect in every way. She has a filly named Princess Guy (which, ok, not the best name but whatever, she has a stallion named Mr. Guy that she loves and named her after) that is setting track records alongside Bonfire, and she has zero compunctions about going where the best races are – at fairs or at the night tracks.

So what does Jimmy think about Miss Elsie?

A month or so ago, Jimmy read on the back of [a newspaper clipping] you’d sent that Miss Elsie Topper had left the Ohio fairs and was racing her black filly, Princess Guy, a,t Maywood Park, the night raceway just outside of Chicago. I don’t have to tell you how Jimmy feels about the night raceways. He bellowed for days that Miss Elsie had betrayed him, and I had all I could do to quiet him down.

Once again, in chorus: fuck you, Jimmy.

“And although it isn’t for me or Jimmy or maybe for you,” George added sincerely, “it’s good for our sport in a lot of ways. Raceways like this all ’round the country mean a lot more people are takin’ to our sport, and in time they’ll learn to love it the same as we do.”

JIMMY DOESN’T DESERVE YOU, GEORGE.

Tom and George enter Bonfire in the Big Race (I don’t remember what it’s called, but it’s a Black Stallion book, of course it ends with a Big Race), pooling the last of their money to do so. It’s a tight race, but please use your best surprised face when I tell you that Bonfire wins. (I snark because I love; Bonfire’s races are arguably the most enjoyable scenes in the book, because they get back to what these books do best.)

They win a ton of money! They pay off all the medical bills, all the feed bills, all the travel bills, they buy ALL new equipment, and Bonfire sets a new record for the mile at 1:59. Happy ending, right?

lol. Remember how they have to go back to their abusive home?

Jimmy Creech stood at the other end of the shed, bellowing fiercely. He was holding the tall gold-plated trophy in his hands, reading the inscription on it. When he had finished he looke dup and saw them; then the trophy came hurling through the air as he hurled it at their feet. It rolled past them, striking with a sharp ring against the door. Bonfire shrilled at the sound of it, then moved uneasily back and forth in his stall. Quickly Tom went to him, going inside the stall to quiet the colt. He ran his hand up and down Bonfire’s head while Jimmy Creech continued raging without making his words understandable.

“You’re here…and that’s the way we wanted it to be. And I wanted you to see this colt race, Jimmy. You’ve never in your life seen a colt like this one…let alone owned one. He’s a world’s champion, Jimmy. He beat the best there is. He did one fifty-nine, Jimmy. Are you thinkin’ of that at all? Or are your mind and body filled with so much hatred for the raceways that you can’t even see a colt like this any more? He’s yours, Jimmy. You bred him. You own him. All your life you hoped this would happen to you…never dreamin’ it would come. But it has, Jimmy…and you’re not even looking at him.”

I wish I could say that either George breaks up with Jimmy and goes and lives his best life, or that Jimmy has some kind of amazing revelation and about-face, but the ending is much less satisfying than that. The only thing Jimmy says is to order Tom to take Bonfire’s blanket off so he can look at the horse, because somehow that’s supposed to be an apology AND a thanks for everything he put them through and they did for him?

I don’t know you guys. This was not a fun book to read. The good parts (training, racing, Tom being sweet if in over his head, Miss Elsie) were totally obscured by the rage that fueled the narrative conflict.

Have you read it recently, or not-so-recently? What did you think?

I am among the least superstitious people on the planet. I don’t really do lucky things. I have things that I like, and things that I have imbued with meaning, but I don’t think the world will go wrong if I don’t have rituals, objects, or anything else that I feel blesses my endeavor. (My husband, on the other hand, has elaborate charts that he uses to keep track of what jerseys he was wearing when his sports teams win or lose so that he can make sure he gets it “right.”)

I’m not in the slightest bit religious, either. I don’t really care whether ghosts exist or not. I’m really kind of boringly pragmatic in a lot of ways. I like to work hard and figure things out and love the things that I love, and mysteries that can never be solved are kind of boring to me.

I tell you this mostly as context to the story I’m about to relate to you, so you can understand how weird it is.

Maybe a month ago, Tristan’s pasture mate was euthanized. He was in his 30s, and he had the variety of health problems you’d expect from an ageing horse. He was exquisitely well cared-for and much loved, but he was getting increasingly neurological. Getting up and down the hills of the farm was hard for him, and getting harder.

I can’t stress enough how hard everyone worked to keep him comfortable and how lovingly the final decision was made. The barn manager brought him out to handgraze with Tristan for a while so they could say goodbye. They’ve been turned out together reliably for a few years now, because they had similar needs for grass (type and/or lack of), because Tristan doesn’t play hard, and because they were just calm and happy together. So it was lovely that they got to say goodbye.

Tristan rarely gets attached to other horses. He has some horses that he likes, especially longtime pasture buddies, but he’s never been a horse to make instant best friends on a trailer, for example, and he’s always been perfectly happy to be turned out alone when that ends up being his situation. For a horse that spent his formative years running wild in a herd, he has an awful lot of loner-like tendencies. I’ve always thought that if I did bring him home with me someday, he’d be content and happy alone for quite a while.

That’s just more context for you.

On Monday, I took Tristan out for a long walk around the field. Nothing taxing at all; just a walk with some nice trots up hills. We’ve circled this field I don’t even know how many dozens of times.

At the end of our ride, we were coming up the last bit of hill, and he was on a loose rein, and he scooted forward, hard and fast. It wasn’t really a spook or a bolt. It was a short launch, a stride or two of energy and alertness. I didn’t even have time to pick up the reins, just sat it with my seat, and he came back to a walk by himself. I thought that it was the new trailers that were parked at the top of the hill, though those had been quite visible for our entire walk up the hill and were no surprise.

I walked him around the trailers a bit, and he was alert but not bratty. Then he stopped and let out a long, loud, neigh. Really long. Really loud. Then again. I was totally baffled – he’s also not a vocal horse. Mustangs rarely are. There were no other horses in sight, no other people, no other animals. Nothing at all.

I was confused but shrugged, and we turned for home. As we were leaving the hill, he called out again, long and loud. This time, there was a horse in the outdoor, so I guessed he’d been calling to her. It’s a mare that he’s never actually “met,” though they’ve been ridden in the ring together maybe two or three times. Still really weird for him to be calling for her, but I guessed that’s what happened.

As I dismounted, a thought occurred to me, and I walked into the barn and poked my head into the tack room for the barn manager.

“Hey S,” I said. “Where is Pari buried?”

I knew generally where the barn buried horses, but S. described to me a spot precisely where Tristan had had his first scoot.

I’m not sure what to think. S. was very close to Pari and thought that Tristan saw something. That’s comforting for her, and it really is a lovely thought. But it’s so far outside of how I usually interpret things that I’m just not sure. Most of my practical brain just thinks he smelled that other horse, or he just had a weird whim.

What do you think?

Satan has won the Triple Crown, but he’s not Alec’s horse anymore. Just when Alec is feeling his most sulky, he learns that Abu Ja’Kub ben Ishak has died and left him the Black! The Black arrives and Alec finds himself wondering which black stallion is faster. He’s slated to get his answer when he learns that ben Ishak entered the Black into the International Stakes, a race pitting the champions of many countries against each other. Before the race is run, however, a deadly disease sweeps through the racing barns.

Like The Black Stallion Returns, the majority of this book’s plot is in its last 50 or so pages. It creeps along like molasses and then it is a lightning storm of plot devices swallowed by plot holes in some kind of endless ouroboros of bad writing. But we’ll get to that.

The book starts with a bang: Alec is in the starting gate with Satan at the Belmont. The colt (who please note is still “burly” compared to the Black, like it’s not enough he has daddy issues, he also gets fat-shamed constantly) has won the other two legs easily, and he crushes this one too. There’s a weird moment in the post parade when some jackass in the crowd snarks Alec for…riding too well?

From the pushing, heaving wave of people at the rail, a man shouted, “Hey, Ramsay! You think it’s a horse show?”

Alec heard the man’s words, but his eyes never left the muddy track which he could see between Satan’s pricked ears.

“A Good Hands class maybe?” the man called again.

Only then did Alec Ramsay become aware that he was sitting much straighter in the saddle than the other jockeys.

Two things. 1) Who fricking cares? and 2) What the hell kind of sadist dreams up a Good Hands class and what the hell kind of masochist enters it? (The internet tells me it’s a saddle seat thing which means the catcaller may have actually displayed some deeper horse knowledge but I’m still staying on record as it being dumb.)

Satan wins, because literally no horse in any of these books has lost a horse race yet. I’ll let you know when it happens.

He was all power, all beauty as he swept beneath the wire, winner by a dozen lengths and the first undefeated Triple Crown winner in turf history!

This book was written in 1951. Confirmed, Secretariat would have kicked Satan’s burly ass. Also – Seattle Slew would’ve at the least tied them.

When Alec gets home from the Belmont, he mopes around pretty much constantly, because Satan isn’t really his horse anymore. And you know what? I actually find this characterization pretty compelling. Alec isn’t actually that that interested in being famous; he just wants to obsess over his horse(s). So it does make sense that he’s feeling possessive and jealous.

I would like here to state my theory of this book, which is: Alec is realizing that Satan was his rebound horse, who he thought he fell in love with because he shared characteristics from his first, abusive, obsessive relationship, but has turned out to be actually a decent horse. Upon realizing this, and realizing that Satan will not be his exclusively, he’s pining for that original relationship that was dysfunctional and unhealthy but at least all-consuming.

Alec closed his eyes, shutting out the Black’s picture from his mind. But he opened them almost immediately, startled by the sound of his own voice as he said loudly, “Today I rode Satan to the Triple Crown championship. No one could ask for more than that. No one should. I’m the luckiest and happiest kid in the world.” He repeated his words to himself, then rose to his feet, knowing well that he was only kidding himself. He wasn’t happy at all.

See what I mean? He’s even talking about it out loud with Henry. Seriously, he either got a personality transplant or some kind of massive maturity upgrade or…maybe he’s finally going to therapy? That’s my headcanon, anyway.

Alec turned to him. “Sometimes, Henry, I think of myself as a baby who’s had his pet toy taken away from him,” he said angrily. “I guess I’m unhappy because I can’t have Satan to myself any longer. I tell myself to grow up, that I can’t make a pet of a champion. I put all the cards on the table. I say this is exactly what I wanted. I’m glad Satan is everything we thought he’d be. I knew from the very beginning that, if he was to be a champion, I’d have to share him with others. I knew his training would have to go on, even though I couldn’t always get to the track to ride him. I knew other fellows would be up on him when I wasn’t. Everything made sense…everything was just the way I’d figured it was going to be.” Alec paused, his gaze leaving Henry for Napoleon. “Yet I’m finding it hard to take…much harder than I ever thought it would be.”

Henry is very pragmatic about all of this, and frankly, this way of horsekeeping makes a lot more sense to him as a trainer who’s been around big horses most of his life. The “shared” model is his default, where for Alec his weird, obsessive relationship with the Black is normal. Hence, Henry has very much come around on Satan after thinking he was the devil. Henry and Satan are now besties, really.

Henry convinces Alec to take down the photograph of the Black that hangs in the barn, because he thinks Alec needs to move on, and it’s not an entirely unreasonable message but he delivers it kind of shittily. He’s honestly kind of a jerk through this whole book which I think might be guilty over-compensation from enabling Alec through the last through books.

Literally seconds after Alec puts the picture of the Black away (LITERALLY. SECONDS.) his father comes to the barn to tell him he has a letter from “Arabia.” Turns out Abu Ja’Kub ben Ishak is dead – he was killed while riding the Black. The letter is from his kickass daughter, who is still going by her maiden name or maybe her marriage didn’t go through after all? Ancillary questions, I have them.

Ben Ishak left a sealed letter saying that in the event of his death the Black would go to Alec, and Tabari notes that but for that they would have put him down which…I feel like everyone maybe should’ve dwelled on that point a little longer? Henry actually points out (more overcompensating!) that maybe the Black has had a few more screws loosened because straight-up killing a man who has been handling him for years is not a great sign, but our Alec is totally undeterred.

The Black arrives in style, on a cargo plane, and is unloaded at midnight by a handler who I think is supposed to be portrayed as abusive but really is just trying to install some manners (albeit roughly) in a very tenuous situation but of course that goes badly. Thankfully the Black recognizes Alec or he would’ve bolted, and as Henry points out.

“If he’d gotten away, everyone on the field would’ve know it, an’ it’d be in the papers tomorrow. As it is, these Trans-World guys are just glad to get rid of him.”

Yes, Henry, if a wild horse had gotten loose on a busy airfield the papers would’ve been the worst part of it.

They bring him home and there’s this great bit:

Running to the van, Henry pushed the ramp inside. He was closing the door when Alec called, “I’ll ride back here with him.”

“As if I didn’t know,” Henry said.

Henry Dailey, bringing the snark!

Everything is immediately back to “normal” for Alec and the Black, and they team up to continue to subtweet Satan.

The stallion moved forward, without bolting, and his gait was effortless and easy to ride. How different he was from Satan, Alec thought. For only when the Black’s burly son was in full gallop was he easy to ride; only then did Satan lose the ponderousness that was so much in evidence at any other gate.

Okay. Guys. Satan is VERY well bred. There is literally no reason for him to be bashed so constantly. His dam is supposedly the specialest and most purest Arabian left (Tabari’s mare Johar) and his sire is the Black. If he still has “ponderous” gaits, Alec, it’s your own shitty riding at fault.

Everyone agrees that it’s very important that no one find out the Black is back, because as soon as it occurs to him that Satan might be faster than the Black, he’ll go nuts and demand to prove it isn’t so. And…yeah, that’s exactly what happens. Satan wins some imaginary race at a mile and a quarter and sets a new world record of 1:58 and Alec just loses any semblance of sanity. He obsesses over it constantly and finally makes up a really dumb plan to to race the Black at the local golf course (living the dream!) where by coincidence he and Henry have measured out a mile and a quarter.

Not only does the Black run the mile and a quarter a full second slower than Satan, Alec gets ticketed by a cop for galloping in a public park. Somehow that never came up in all the times he and Henry exercised Satan along that same trail? The cop is also really dumb and is generally jerky and threatening, so of course the Black takes exception and tries to kick him, which just exacerbates the whole situation.

A few days later, Alec shows up to pay his fine – he has to appear in court for it, for some reason? He gets questioned by a reporter, who guesses who Alec is and then this whole plot cascade that makes NO SENSE starts in which Alec becomes convinced that everyone is on to him and will know it was the Black.

As he pulled [the gate] open, he knew what hew as going to do, and he didn’t have any time to lose. The reporters would be here within an hour, maybe less.

Okay. Realistically, though? The Black won one race (albeit spectacularly) four years ago. I know that horse racing has fallen out of the American public eye, but not even Tom Brady would get this much media attention if, say, he dropped out of the public eye for four years and then showed up throwing around a football in a public park.

Nevertheless, Alec tries to hide the Black in the tack room and to convince the six (SIX!!!) reporters who have shown up that he was actually galloping Napoleon. The journalists are all super weird and invasive and for some reason Alec just caves in and shows and tells them absolutely everything they want to know? Alec doth protest too much, I think, because not once does he say something like “private property” or “nope, not today” or literally anything like that.

It’s our old friend Jim Neville who finally moves our plot forward: he says that before he died, ben Ishak entered the Black in the upcoming International Cup, a race between champions of every country. Satan’s already entered, of course. He pressures Alec to race with a really weird argument that he repeats multiple times, even though Alec keeps saying that their plan is to take the Black to a farm upstate and put him out to stud.

“Why don’t you race him then, Alec?” Jim’s words came fast; he was taking advantage of Alec’s pride in the speed of the Black. “I’d like to see it….So would everyone else.” He paused. “Don’t you think you owe it to racing?”

A) no, Alec doesn’t “owe” anyone a goddamn thing

B) if literally anyone in these books valued good ground manners 5% as much as they valued speed, I would have a billion times more respect for them

Alec is suckered into saying he’ll go ahead with racing the Black in the International Cup, which makes the front page of all the newspapers the next day. Cue a whole chapter in which Alec basically goes back and forth showing the Black to the public. Seriously, people just show up at the front gate of the farm and Alec spends every waking second walking them down to the barn, two at a time, letting them see the black, and then walking them back. Alec clearly hates every second of this but he keeps doing it. For reasons.

Henry gets back while Alec is in the middle of trudging back and forth and true to his more sane, curmudgeonly personality in this book, he immediately thinks running the Black in the International is a terrible idea.

“He could raise havoc on the track, and that wouldn’t do the sport any good either. There are some mighty valuable horses in the International, Alec, an’ I wouldn’t want to be responsible for any damage done.”

Who is this person and what has he done with Henry Dailey?

Alec ropes Henry into his obsession and there is a totally fascinating exchange.

“What do you think, Henry? Could Satan beat him?” The Black pushed his muzzle toward Alec’s pocket, seeking a carrot.

“It’s not fair to ask me that, Alec,” Henry said, after a long silence. “You know how I feel about Satan.”

“You mean you’re closer to him than to the Black.”

“Guess you can call it that. I’ve done something with Satan. He has the Black’s speed and he’ll turn it off an’ on for anyone on his back. It’s a combination hard to beat…for any horse,” he added, turning to the stallion.

18 months ago, Henry thought Satan was the devil himself and that he might have to be destroyed, but I guess a Triple Crown changes everything? So on the one hand, this change makes absolutely no sense. On the other, I do think there’s something to Satan having changed into a horse that Henry understands much better and Alec understands much less, and in that way, I do buy this.

Here’s how I can make an argument for Farley having finally upped his writing game in this, his fifth book: there are legitimately thoughtful themes that carry through this entire book. The pacing still blows chunks, but you can truly trace a dichotomy of points of view through the book. Henry represents the status quo, straightforward success, reasonable goalposts, good training, and civilization. Alec is much more interested in a primal way of understanding horses: it’s pure emotion and longing, wildness as a virtue, and rampant ambition to be the very best. You can really understand why they don’t see eye to eye about the two horses in their lives, and why I really think it’s a great idea that Alec announces his intentions in this book to retire to their new breeding farm and manage that.

(Okay, it’s also a really terrible idea, because Alec – who still hasn’t finished college! – knows jack shit about breeding, business, barn management, or really anything about horses beyond galloping them around recklessly. But on an emotional level I can see why it works for him.)

Henry gets Alec to agree to pull the Black from the race if he acts up, and they set off.

[The Black] was halter-tied to the small open window of the driver’s cab, and Alec was able to reach through it and touch his horse.

What the hell kind of van is this? Who ties their horse TO A WINDOW?

Along the way, we learn about the geniuses behind the International Cup. The track, by the way, is somewhere north of Saratoga. Saratoga is pretty damn far north, you guys. A brand-new track even further north? I call shenanigans.

“How come they’re holding the Cup race there, Henry? Why not at Belmont or one of the other tracks closer to a big city?”

GREAT QUESTION, ALEC!

“Because the International was their idea. And what better send-off could you give a new track than to sponsor such a race? I guess the track’s board of directors figured it that way. And the International Cup race is just before their first regular meeting, so the people coming to the International will most likely stay on for the meeting.”

This makes so little business sense that critiquing it is almost like shooting a fish in a barrel, but *cocks shotgun.*

Okay: the plan is to sponsor a massive international race at a track in the middle of nowhere as the very first thing ever done at a new track. It’s the only race not only on its day but in that entire week. And their hope is that people will come out to the boonies, watch this one race, stay for a full other week, and then hang around for the next week’s race? I just. To be a fly on the wall at that bankruptcy hearing…!

Alec is right there in dreamland with them.

“I wonder if they’ll know each other?”

“Who?”

“The Black and Satan.”

Henry smiled. “No. They’ve forgotten all about each other. Satan was only a few months old when they were separated.

Alec turned to the Black. “Anyway, it’s going to be interesting to watch them together.”

“Yeah,” Henry muttered. “Mighty interesting.”

LOLOLOLOL.

Things start to happen very quickly after this; remember what I said about plot devices chasing plot holes? Well, in defiance of international quarantine, common sense, veterinary best practice, and any kind of sanity, it turns out that El Dorado, the horse from South America, has been running a high fever and isn’t feeling well. He’s better now, though, so it’s totally cool.

“I wonder if you could loan us one of your pails?” the man asked. “El Dorado banged up ours yesterday.”

“Sure,” Alec said, leaving the stall.

The man followed him. “We’re getting a couple more, so I’ll return this to you by afternoon,” he said when Alec gave him the pail.

Oh. My. God. This makes so little sense that my only plausible explanation is some kind of sinister industrial espionage. Maybe there’s a conspiracy among the owners to chase insurance money? A racing stable that houses the South American champion (yes, in this world, like Arabia, South America is one country) does not have extra buckets? So they go begging from down the aisle? And then say they’ll return it? AFTER THEIR HORSE HAS BEEN SICK? Sweet zombie Jesus on a pogo stick.

Soon after that, Satan (I’m sorry; “the burly colt”) arrives and loses his brain because he sees the Black. Of course they want to kill each other. Literally no one but Alec thought they would have a touching slo-mo soaring music reunion.

And as Alec remained with his horse he thought of how much he had looked forward to the day when the Black would meet his colt. He’d even thought they would recognize each other for what they were, father and son. But it hadn’t worked out that way at all. There was no love between them. They were two giant stallions, both eager and willing to fight. No, it wasn’t the same as he’d thought it would be at all.

You know, I’m almost a little sorry for Alec; the narrative requires him so be so unfathomably stupid.

Henry has a theory that the Black “brings out the instinctive savageness and hatred in every stallion to fight his kind.” Which is obviously bullshit, but he’s not wrong that the Black can’t be trusted around other horses, and he loses his marbles when Alec tries to work him on the track. Thankfully, Alec sees sense and agrees to withdraw the Black from the race, and holds firm when Jim Neville tries to bully him into going through with it. They’re going to leave in the morning.

Except they’re not! The plot continues to move at the speed of light in the background.

“It’s serious, Alec,” Henry said solemnly, turning to the boy for the first time. “El Dorado has swamp fever, the most dreaded horse disease known. They’re putting him down tonight,” he added quietly. “There’s no cure…it’s the only thing they can do.”

Now, fully expecting Walter Farley to have made up some bizarro disease, I faithfully Googled “swamp fever” and to my amazement: it’s an old name for EIA, equine infectious anemia. That’s the disease that the Coggins test looks for. There’s still no cure, and infected horses are still destroyed. I found this long PDF from the USDA to be a great read about a disease I really hadn’t thought a lot about. It’s largely gone from the US horse population today thanks to aggressive testing and isolation, but it was absolutely a very realistic fear in 1948. Kudos to you, Walter Farley! Too bad you didn’t put that kind of thought into international quarantine procedures, or you would never have had a book.

Alec finally realizes that lending a bucket to El Dorado was a terrible idea, and loses his shit. Henry is cool as a cucumber and points out that the odds are in their favor.

The vets, meanwhile, have been paid off by plot device and have decided on the most cumbersome, most suspenseful way possible to proceed.

“The only definite way we have of finding out is to take blood samples from your horses and, pooling this blood, innoculate it into the bloodstream of a horse who has not been exposed to the disease. If no evidence of the disease appears in the innoculated test horse, your horses will be given a clean bill of health and released. However, if swamp fever develops in the test horse, each of your horses must be tested individually to find out which one or more has the disease.

THAT MAKES ABSOFUCKINGLUTELY NO SENSE NONE. NONE AT ALL.

But wait! Remember plot device? Our good friend, racist caricature Tony has arrived with Napoleon in tow. He wants poor Napoleon to be the one that get the Black and Satan’s blood.

“My Nappy…I’m sure he wants it this way,” Tony said more soberly. “He’s-a like brother to the Black and Satan. And now he will have their blood in him. It’s the only way, Meester Veterinary.”

No. No. No. No. No. Christ, poor Napoleon suffers more than any other character in this series with the possible exception of Mrs. Ramsay (whose only appearance in this whole book is to look “plump” at the Belmont back at the beginning).

All the horses are moved to a state quarantine farm even further upstate, and they wait for forty days. Cue montage of Alec spending a lot of time moping around, taking care of the Black and Satan, basically all alone because everyone else has peaced out. (After the vets said for them to leave their forwarding addresses, because 1948!)

It’s fine, though: everyone is healthy! They all make plans to leave the following morning to this long-awaited breeding farm, but plot device strikes again: Alec wakes up in the middle of the night at the hotel to smell smoke and see a forest fire in the distance. He and Henry drive to the farm to see the flames almost there. The vets have let all the horses out, but they’re all just hanging out in a field, except the Black. Alec lets the Black out, but Satan won’t come with them, on account of his daddy issues.

They start to leave but Alec turns back around, and Jim Neville (who just…randomly showed up?) has to restrain Henry from following him, and they both drive away, leaving Alec to his equine-assisted suicide.

Alec uses the Black to chase the other horses to a gate he saw earlier, that leads to a lane that…well, he has no idea where it leads, but at least he admits that in the text.

What follows is a genuinely suspenseful and exciting race through a forest fire. Yes, it’s beyond dumb that all the horses are a-ok with galloping pell-mell through flames, but I would argue that actually this scene works overall. Especially since the point is less to get away from the fire than it is to provide a contrived set of circumstances in which the Black and Satan finally get to have their match race.

Rather than recap the race, I would like to type out the best passage in the book, and perhaps the best scene in the entire series. (If you really need to know, the Black wins by pulling ahead at the last moment.)

“Satan was behind the others when I saw you. Did he catch any of them, Alec?”

“He did, Henry.”

“Then you think he could’ve beaten the in a race. Is that right, Alec?”

“He did beat them, Henry,” Alec returned quietly.

“Y’mean he made up the whole distance?”

Alec nodded.

“I knew he could do it,” the trainer said proudly. “I just knew he could!” It was a long while before Henry asked hesitantly. “Was the Black able to catch ’em, too?” His face was tight-lipped, intense.

“Yes, he did,” Alec returned slowly.

After a long pause, Henry said, “It was a lot to ask of him, carrying your weight.” The trainer turned again to the rear-view mirror and his husky jowls worked convulsively as he added huskily, “Too much of a handicap to expect him to catch Satan as well.” He turned to the boy. “Not a colt like Satan.”

Alec raised his eyes quickly to meet Henry’s gaze. Without hesitation he said, “No, Henry…you couldn’t expect that of him.”

Henry’s heavy jowls relaxed; his tight lips parted in a smile. “We’ve got the finest horses in the world, Alec,” he said almost in awe. “They don’t come any greater than those two. We know that now.”

No objectivity from me, I straight up have tears in my eyes every time I read that scene. Everyone thinks their horse is the best horse in the world, and no one is wrong. Alec, building on the emotional maturity he’s slowly started to achieve through this whole book, reads Henry like an open book. He doesn’t say that Satan lost; he just lets Henry think what he wants, and he just shuts the hell up. He knows the Black is faster, and he’s the only one who needs to know.

They pull in to Hopeful Farm, and just as they’re arriving in the driveway, Henry asks if Alec would do him a favor, and breed the Black to his friend Jimmy Creech’s harness mare. Alec agrees…and we will cover the stupidity of that decision in the next book, The Black Stallion’s Blood Bay Colt.

Steve visits his childhood friend Pitch on the Caribbean island of Antago after Pitch sends him a newspaper clipping of wild horses on nearby Azul Island. They discover a hidden herd of wild horses, loads of Conquistador artifacts, and one magnificent chestnut stallion that Steve names Flame. Steve tames Flame, and Pitch and Steve witness a duel between Flame and a piebald stallion who also seeks to lead the herd. They decide to keep the island their secret, and return there whenever they can.

The first thing I need to say about this book is that Steve and Pitch are both unutterably, insanely, disturbingly, weird. SO WEIRD. They have half-formed personalities that basically shift constantly and how on earth do they deal with basic social norms and other people? In short: they are both really badly written.

The book starts by placing Azul Island with precise latitude and longitude coordinates.

Steve is arriving to spend a few weeks with his childhood friend and next door neighbor Pitch, who has moved to the island of Antago to live with his older stepbrother, Tom, who owns a sugar cane plantation. Before we even go on can I just say that at no point does anyone in this book grapple with or even mention the history of brutal conquest and slavery that was the Caribbean sugar industry? Yeah. Here, read about it if you want to get (even more) depressed.

Anyway, Tom is a dick, but he at least has a well-defined character and a narrative purpose in the arc, because he thinks Steve’s proposal to spend two weeks camping on Azul Island is dumb and he tells Steve that if he can hack it for two weeks he can have any horse he wants. It’s not clear why he thinks Steve can’t hack it, other than he’s the kind of guy who doesn’t think anyone is competent at anything. In fifty more years, Tom is going to be hanging around internet forums posting Pepe memes and calling people cucks.

Let me give you a taste of how weird Steve & Pitch’s interactions with. This is one of their very first interactions after being apart for several years.

Steve pointed to Pitch’s shorts and said, smiling, “And you couldn’t get by with an outfit like that at home.” “No,” Pitch returned very seriously, “no, you couldn’t at all. And it’s a shame, for they’re so comfortable.”

…shorts? You can’t wear shorts in America? I mean, I know that standards for men’s clothing have changed and Steve and Pitch are both at a precarious point when they’re not yet full adults and therefore are navigating the boundaries between acceptable young adult clothes and acceptable adult apparel but I somehow don’t think that’s what Walter Farley was trying to say here.

Pitch’s eyes were bright as he went on excitedly, “From here, Steve, those infamous Conquistadores, men like Cortés, Pizarro and Balboa, may have selected their armies, their horses, guns and provisions, and set forth to plunder the Incas and the Aztecs of their gold!”

WHY ARE YOU EXCITED ABOUT THAT, PITCH?

The Conquistador fanboying also leads quite nicely into the other theme of the book: equine eugenics. And look: we select for traits when we breed, and as humans who control the breeding destinies of our animals, we are obviously creating what we want, and I know that the term eugenics doesn’t quite apply in the same way. But there is a difference between “selecting for desired traits within a breed standard that is part of a wide array of different breeds” and the over the top bizarreness that Steve and Pitch engage in here. I’ll provide examples as we go on, but here’s one of the first, when they arrive on the sandy beach that everyone thinks is the only accessible part of Azul Island.

It was obvious that Tom had left the worst of the horses upon Azul Island, Steve thought. Certainly the Conquistadores couldn’t have ridden puny animals like these in their long, arduous campaigns into the New World! He remembered the pictures of statues he had seen in his schoolbooks of men like Pizarro and Cortés sitting astride horses strong and powerful of limb, capable of standing the rigors of long marches through strange and hostile lands.

Pretty is as pretty does, Steve, and basing your conceptions of history off of pictures of statues from elementary school textbooks is…really dumb.

Speaking of the island, can we talk about its ecology for a second? Azul Island is about 95% steep canyon walls (how steep? steep enough to block the sun, but not so steep that Steve & Pitch can’t climb them by hand later) with a sandy beach a few hundred yards wide by a quarter mile long that is believed to be the only accessible part of the island. On this beach lives a herd of horses with such viability that Tom can round up 30 horses every few years from them. How do they not all starve to death? Great question! Never answered.

Then we get to the next part of the story, in which Steve finally confesses to Pitch why he came to visit him in Antago. Pitch had sent a newspaper clipping of the most recent roundup of Azul Island horses, and it reminded Steve of a literal fever dream he had as a small child.

It was the anaesthetic, but I didn’t know that. I breathed in the sweet, sickly odor, and I was still thinking of my pony when the fiery pinwheels started. I followed them round and round as they sped faster and faster. Soon they were going so fast that they no longer made a circle, but were one ball of fire. It came at me hard, bursting in my face. “It was then that I first saw Flame. I didn’t name him Flame. The name just came with this horse, for his body was the red of fire. He was standing on the cliff—” Steve stopped and glanced behind him. “That cliff,” he added huskily. “Below, too, was the canyon and the rolling land beyond. All this …” His hand pointed to the canyon and then fell to his side.

[…]

“I grew up,” Steve went on, “and put Flame aside along with my tricycle and scooter. But I never actually forgot him, Pitch,” he insisted. “I never forgot Flame, or the canyon and cliff. Then a few weeks ago your letter came—your letter with the picture of a place I’d thought an imaginary one for so many years!” Steve’s voice had risen and there was eagerness in it now as he turned toward Pitch. “How could I have seen this canyon ten years ago, Pitch? How could I, when I’d never heard of Azul Island until a few weeks ago when your letter came? That’s what brought me here, Pitch,” he confessed.

So of course that very night they wake up in the middle of the night and what do they see? A giant chestnut stallion standing on that very cliff! (Later in the book it will be pretty clear that there is no way to get to the top of the cliff from the inside of the island except by climbing up a rope. Pretty much everything to do with this island is a plot hole so large you could drive a dump truck through it.)

This sends Steve straight into a frenzy, and they pack up their campsite and circle the island in the hopes of finding where the horse came from. They find a rock that they tie up to, and then foot and handholds up a fissure in the rock that they climb up. At the top of the cliff is a man-made hole, and they rappel down it into some caverns. Then they wander through the caverns for hours and hours. At one point they stumble across a room entirely full of skeletons chained to the wall. The lose all their matches, and then their flashlight. Because there is no justice in the universe, they do not starve to death.

“This tunnel is partly natural in formation, Steve. It could have been cut as far back as the Ice Age, then pushed up by some giant upheaval.” Pitch paused, then added with great awe, “But a lot of it has been worked out by hand. Notice the perfect regularity of the cutting on each side and on the ceiling here.” Steve’s eyes were following the beam of light. “By whose hands?” he asked. “The Spaniards, Steve, the Spaniards,” Pitch returned quickly. “They probably started work on it early in the sixteenth century and continued for well over a hundred and fifty years—until shortly after 1669, I’d say.”

Can I just get this off my chest? All the online summaries you read about this book call Pitch an archaeologist. PITCH IS NOT A FUCKING ARCHAEOLOGIST. He is an overly enthusiastic amateur idiot. We have no idea what he does on Antago other than skulk around his stepbrother. He has a creepy hard-on for the Conquistadors and he digs shit up. That’s it. He’s an archaeologist in the same way my husband is an electrician which is to say my husband wanders through the house leaving lights on for hours at a time and unplugs my iPhone chargers at the worst possible moment. Pitch jumps to bizarre conclusions, has no sense of context, has no interest in interrogating or documenting the things he finds. He’s a worse archaeologist than Indiana Jones, who at least managed to get a doctorate and puts things in museum collections occasionally.

They emerge into a magical valley that comprises (most of) the interior of Azul Island, and there they see a band of horses! What kind of horses, you ask? Well, if you’ve read my other reviews you know that Walter Farley is obsessed with typing every possible kind of horse as an Arabian, no matter how unrealistic or unlikely it is that they would be.

Leaving the herd, moving from shadow to sun, stepped the giant stallion of the cliff! He walked toward the pool, his proud head raised high, his muscles moving easily beneath sleek skin. The sun’s rays turned his chestnut coat into the glowing red of fire. Under his breath, Steve murmured, “Flame!”

[…]

“They all have Arabian blood in them, Pitch. Notice their wedge-shaped heads.” And then Steve went on to point out every physical characteristic of the Arabian that he had observed in the horses. He concluded by saying, “They’re the same horses the Conquistadores rode centuries ago, Pitch.”

One of them does the math and realizes this single herd of horses has been here for ~300 years, which is…interesting. Steve’s fine with it.

But I’ve read,” he went on, “that inbreeding is perfectly all right if the horses are of the purest blood and don’t have any bad traits or weaknesses; because if they do, the bad traits in both sire and dam show up in the foal worse than ever.” Steve paused. “But that hasn’t happened here—at least, as far as we can tell.”

…that is not how genetics work, Steve.

They watched the horses for a few more minutes before Pitch said, “I was thinking of the Arabian blood in these horses, Steve. You know that seems logical to me too, now, because the Arabs invaded Spain in about 700 A.D. They remained in Spain for five hundred years before they were forced out, and I’m sure that by that time their horses had become native to Spain.” Pleased with his own reasoning, Pitch looked at the horses with renewed interest.

…that is not how history works, Pitch.

The next sequence of events is super weird and really kind of awful. (I feel like I’m overusing the word weird in this review, but at the same time I feel like my review is making this book feel more coherent than it actually is. Imagine me writing and erasing “weird” about twice as often as I actually ended up using it.)

First, a bay stallion comes out of nowhere (nowhere!!! there’s only one herd of horses!) to challenge Flame, because if there’s one thing this book series has established, it’s that stallions are crazed assholes who fight to the death at every opportunity. Probably 10% of this book is horse-on-horse MMA. Flame kills the bay stallion, and then another stallion emerges out of nowhere to challenge Flame.

Then he, too, saw the monstrosity of a horse that now stood a few hundred yards from the red stallion. He had come with the falling of the sun behind the walls of Azul Island. In the shadows, his massive body penetrated the darkness like a luminous thing. It was as though he belonged only to the night. He was as grotesquely ugly as the red stallion was beautiful. Thick-bodied, he stood still, waiting … waiting as he had done all through the fight of the other two stallions. Small, close-set eyes—one blue, the other a white wall-eye—gleamed from his large head, which was black except for the heavy blaze that descended over his wall-eye. His neck was thick and short, as was his body, and black too except for the ghostly streaks of white that ran through it. His mane and tail were white. Arrogant and ruthless, fearing nothing, he moved toward the red stallion at a walk, hate gleaming in his beady eyes. His heavy ears were pulled back flat against his head, his teeth bared. Suddenly he stopped, with ears pitched forward, and screamed his challenge again. He was the embodiment of ugliness, of viciousness. Only the high crest upon his neck and the high set of his tail gave evidence of the Arabian blood in him.

Read that description, and then read it again slowly. Yeah. It makes even less sense the second time, doesn’t it? You see what I mean about equine eugenics now? The Piebald actually sounds like a horse I’d rather ride than Flame, to be honest. Good bone, cool coloring, a bit sassy but way smarter than Flame. Sure, he’s supposed to be the embodiment of evil, but Flame doesn’t exactly have moral high ground to stand on either.

The Piebald kicks Flame’s ass, and Flame runs away and disappears at the far end of the interior canyon. Steve is apoplectic and convinced that the Piebald will ruin the herd of horses in the valley by spreading his inferior seed, and it will be the end of this majickal breed of horses because nothing like this has ever happened in the last weird incestuous 300 years of this herd being entirely alone. (With no natural predators, and a couple square miles of grazing space! How is this place not ten feet high in horse bones?)

Steve, of course, follows Flame, and as he does so somehow the geography of Azul Island gets even more confusing. He goes through a narrow passageway to find another small canyon, where Flame is hiding out. Then Flame runs away from him into another narrow passageway, and emerges into a huge natural sea cavern. There are all sorts of small caverns off the main one, and in one of those small caverns is a pit of quicksand. With a sort of…winch over it? Like the Conquistadors used to…lower things into it? Is it some kind of torture mechanism? Why quicksand? What the actual fuck?

Of course Flame falls into the quicksand, somehow. (I’m honestly not sure how. I think trying to escape Steve? Good job, jackass.) Steve gets a rope around him and stops him from sliding further in. The rope is hooked to the 300 year old winch mechanism, which works perfectly. Then Steve leaves to go get Pitch.

Pitch thinks the whole thing is weird, and could Steve just calm down for a bit and have some dinner before they go rescue Flame?

“I didn’t mean to be unkind,” Pitch said quickly. “I’m sorry, Steve. It’s just that I’m finding it difficult to keep pace with your reasoning. Why are you so certain that Flame won’t return to his band?

Pitch is all of us.

Then I’m pretty sure he roofies Steve because…Steve falls asleep. Just out cold. While Flame is dangling from a winch in a pit of quicksand on the other side of the island. Holy shit.

When he wakes up, he has to talk Pitch into going to help him, which Pitch eventually does, and on the way there they do a lot of little side trips to look at Conquistador stuff because Pitch’s hard-on continues unabated. In order to get Pitch’s help, Steve promises specifically that he won’t pursue Flame anymore, because Pitch is worried (not unreasonably!) that Flame is a wild animal who will kill Steve. Steve promises, and then spends pretty much the rest of the book whining about that promise.

They rescue Flame in a harrowing and highly improbable sequence of events, and then we get a whole long montage in which Steve makes heart-eyes at Flame from across fields while Pitch digs up extraordinary artifacts and just puts them in his pockets because they’re shiny. That’s maybe 10 days of their 14 day trip. (Everything else I have recounted was days 1-3, yes, seriously.) Eventually Flame approaches Steve and Steve says that he hasn’t violated his promise to Pitch because he didn’t pursue him, Flame came to him! That seems like really weaselly logic to me, but whatever. Steve then spends all day riding Flame and fixing up his cuts from his fight with the Piebald.

Steve is pretty determined to get Flame off the island, because he thinks Flame can be the horse that Tom promised him. He thinks that Flame is now ostracized from the herd and he doesn’t care about equine racial purity anymore, just about “his” horse. He’s convinced that Flame is to afraid of the Piebald to go back into the main valley.

Pitch and Steve get ready to leave on their last day, and the last 10% of the book is just them making up, and then changing, their minds about whether or not to tell people about the island. I wanted to knock their heads together really hard many times during this sequence. Make a plan and stick to it, fer fuck’s sake!

But no! Flame follows Steve out of the valley like a lovesick puppy, whistling/screaming/making impossible noises the whole time! And the Piebald sees him, and Steve and Pitch. He chases down the boys and breaks Steve’s arm somehow (maybe by knocking him over? it’s really not clear). We get another multiple-page long stallion fight after which Flame finally emerges victorious, shockingly enough, and that convinces Steve that Flame has to stay on his island.

They get back to Antago in the boat which has miraculously been tied up to a random rock on the side of an island in the middle of the Atlantic for two weeks without sustaining any damage or sinking, and Pitch changes his mind five more times on the way there about whether to tell people.

Steve finally makes a vanity appeal, saying to Pitch that he could be the only person to study the island and he could make genius archaeological discoveries and Steve will come help him whenever he can! On all his school vacations and summers! Pitch thinks that sounds just swell, and he’s going to excavate an important untouched archaeological site entirely by his untrained and uninformed self and everyone will be just thrilled!

Aaaaaand…end book. Seriously, that’s it. What a long, strange trip that was, from the fever dreams to the equine racial purity to the Conquistador wet dreams to the utterly unlikable personalities of…literally everyone. Do I even need to mention that there was not one single woman in the entire book? Not “no women who spoke” or “no women with names” but not a single solitary woman even in the background. Oy.

I feel like I should say a few good things here, and what I have to say is that the most appealing parts of this book are pure wish-fulfillment. A secret tropical island with a hidden valley and a herd of magical horses? Sign 12 year old me! (Hell, sign 34 year old me up.) Obsessing about the Conquistadors at least gives Pitch something to do with his sad, weird life. And of course, the boy-and-his-horse trope is still strong here. The wistful, “I have a secret place were I’m accepted and loved” vibe is strong here, and there are moments when it really works.

Next up, I will have to try and be snarky about The Black Stallion and Satan, my own personal childhood favorite.

Alec is gifted the first foal by the Black, a colt he names Satan, but there’s something wrong. Satan has a mean streak a mile wide, and Henry doubts it will ever be cured. After many, many, many violent interludes, Alec eventually bonds with Satan, and they train him for the track. He overcomes training problems and villainous machinations to win the two year old Hopeful Stakes and start a great racing career.

Much like the key to The Black Stallion was understanding that Alec has PTSD, the key to understanding this book is that Walter Farley wanted to try his hand at writing a horror novel but have it all turn out okay after all. There’s just no other way to explain how Satan is written.

Let’s start at the beginning, our third visit to the port of Addis, where a mysterious group of Arabs load a young colt onto a steamer ship. Two sailors watch, and decide a) the horses are really super nice and b) the colt is 5 months old and already a complete shit who bites one of his handlers.

The two sailors also helpfully spend several pages recapping the first book, including telling the reader that the Drake went down with all hands on deck, which makes yet another retcon. I don’t have a good explanation for why I care about this so much except it’s just so damn lazy. Read your own books, Walter Farley! They’re not all that long, it’s taking me about two hours for each one!

Cut to Flushing, where Alec helpfully catches us up on the events of The Black Stallion Returns via internal monologue and also lets us know that Henry is off working for Peter Boldt, “who has one of the finest racing stables in the country,” except his wife is still Alec’s neighbor and didn’t Henry retire and what in God’s name did he do in “Arabia” that merited offering him a job? Wouldn’t Volence be the one that would actually be impressed by Henry? I give up.

Anyway, this is just a way of getting to the real moral of this book, which is that no one in this entire narrative deserves Alec’s mother, Belle. (We only learn her name in an aside toward the end of the book, fuck you, Walter Farley.)

She was afraid. Afraid of what this new horse would bring. Twice before a horse, his horse, had led Alec to undertakings few men had ever experienced. Undertakings which for him had been adventurous, exciting. But for her and her husband, they had meant months of anguish and concern.

I grant you, this is exceptionally poorly written, but augh, Belle. She basically spends this entire book quietly in agony and if anyone acknowledges her at all its either as a joke or as an obstacle to get around.

Speaking of obstacles to get around, Mrs. Dailey, Henry’s wife, who never does get a name!

“Mrs. Dailey?” Alec smiled. “Dad! Don’t tell me you’ve forgotten…Henry’s wife…lives in the big house on the corner, and owns the barn and field.”

“Oh, yes! I guess I’m getting old, Alec,” Mr. Ramsay said, laughing. “Come to think of it, your mother has been charging me with forgetfulness of late.” A slight pause, and he added, “I shouldn’t have thought Mrs. Dailey would make you pay anything, though, what with Henry having that good job on the coast, and her taking in boarders.

Later events will bear this out, but Mr. Ramsay? IS THE ACTUAL WORST. Holy shit. They’re rolling in it, he’s got a job and everything, why won’t they feed your horse for free?!

The colt arrives, and things are…not good. First, he almost kills Alec’s dog, and then Alec gives him daddy issues on, like day one.

Still looking at the blazing eyes, he said softly, “You’re fire, boy. You’re full of it, just like him. You’re mine, boy. We’re going places together…you and I. We’re going to use that fire to burn the tracks. We’re going to make him proud of you. He’ll hear about you, boy. Hear the pounding of your hoofs, even though he’s way back in the desert. It’s going to be the way he wants it, boy.”

For my money, this right here? This is the moment that the colt decides the only solution to his current predicament is to murder everyone, and I do not blame him one bit.

Just for the WTF-ery, I will also give you this bit.

“He’s it, Henry!” Alec almost shouted. He’s everything we hoped for. I know he is. I can feel it right here in his muzzle even?”

JESUS CHRIST ALEC WHAT DOES THAT EVEN MEAN?

Alec announces he’s decided to name the colt Satan, which…do I even need to explain the ways in which that is a terrible idea? Is anyone even mildly surprised that the next ~75 pages of the book are a descent into a storyline right out of The Omen?

What, you think I’m exaggerating? Literally the next whole segment of the book is a see-saw between Alec expressing the same sentiments as above (he’s perfect! he’ll come around! I lurrrrve him! the Black will be so proud!) and Henry saying and thinking things like, well:

And it was his eyes that Henry looked at more and more often as they walked along. They were smaller than his sire’s, and the glare from them was fixed and stony. They bothered Henry. For throughout his life the old trainer had prided himself on being able to tell much about a horse from his eyes. And he didn’t like what he saw in the black colt’s. Too much lurked there…craftiness, cunning, viciousness, yes…and something else, too. Something which Henry couldn’t figure out. Something which he could only feel…and it was sinister. He’d never seen it in the eyes of any horse before, even the Black.

Satan is indeed a little shit, but can you blame him? He’s being trained by an 18 year old kid who has no idea what he’s doing, he gets barely any turnout, he has no interaction with other horses of any kind (he went after Napoleon and so they keep him far away) and basically his only entertainment and enrichment is trying to murder the people around him. Which he does. Over, and over, and over, and over, and…well, you get the idea.

The colt rose above them all in all his savageness, his blood on fire and the urge to kill great within him. No longer did his eyes smolder with contempt. Now they were alive and gleaming red with hate. And Satan’s black body trembled with eagerness as his savage instinct drove him toward the kill.

There’s something deeply ironic about the way Satan is handled, because you know what he needs? He needs a mare to kick the shit out of him and teach him some manners, and he needs friends. That’s basically what Alec needs in his life, too. His mother is abused by the narrative and not allowed to express human feelings without being mocked by the men around her, and Alec spends the whole book isolating himself even further than he already was. He rebuffs the last of his friends who want to spend time with him and then transfers to community college so he can have even less claims on his time.

Anyway. Henry manages to get Satan sort of leading, and there’s a whole bit where Alec sees a length of chain and is worried Henry is beating the colt, but of course Henry isn’t, so with that resolved, Alec looks at a 17hh yearling (not making that up, it’s explicitly stated) that can’t even be lead and won’t stand still for grooming and still tries to bite, kick, or run down everyone around him and well, you know what Alec does, right?

He convinces Henry to put a bridle and saddle on Satan and then gets up on him all within about…an hour? Henry even flat out says this is too fast, but maybe it’s also a good idea, because Satan is so awful this won’t give him time to plot. Jesus, none of these people should be allowed around horses.

Predictably enough, Satan rears and then I think we’re meant to understand that he deliberately flips on Alec and tries to squash him on the way down. Henry later remembers it this way:

Never would Henry forget the hideous sight of Satan, in all his fury, intentionally falling over backwards, hoping to pin the boy beneath his giant body. Never had he seen it happen before, with any horse, and he hoped never to see it again. If Alec hadn’t kept his wits, if he hadn’t been the horseman he was, he wouldn’t have thrown himself clear of Satan’s back as he’d done, and just in time.

Can we be clear about something here? Alec had never touched a horse until the summer he spent with his uncle in India. He pretty explicitly says that in The Black Stallion. Then he rides the Black for maybe a couple of months. THAT’S IT. That is the sum total of Alec’s entire experience with horses. Satan is maybe the fourth or fifth horse he’s ever ridden. EVER.

Mr. Ramsay said quietly, “I know better, Henry. Alec is too good a horseman to fall off, with or without stirrups. You had trouble with the colt.”

Because, see, Henry brought an unconscious Alec to his parents’ house saying only that he’d fallen and hit his head. Also, fuck you, Mr. Ramsay. Alec is not any kind of horseman and far far far more talented riders than he have fallen off. Like me, for example. And probably you. Yes, you! If you’re reading this, you’re probably a better rider than Alec Ramsay!

Alec’s accident prompts Henry to go out and have a come to Jesus session with Satan, and let’s bullet point out what Henry does here because it is so mind-blowingly awful and misguided and just plain dumb that if you’re surprised at how it ends I don’t even know what to say to you.

Turning to Alec, [his father] added, “Don’t mention my buying these riding silks to your mother, Alec.” Pausing, he said confidingly, “She wouldn’t understand.”

Nodding, Alec smiled. “Yes, Dad, I know…she wouldn’t understand.

It literally never occurs to anyone in this book to talk to women like they are people. But she gets her revenge.

Only half-heartedly had she helped search for the paper. She hadn’t wanted to find it. She didn’t want to spend next Saturday afternoon waiting at home, thinking of her son riding Satan in that big race. It would be dangerous, and she was afraid for him.

Only person talking sense in this whole book? Yes, I think so. Notice, too, how she assumes no one will want her there to watch the race? Women’s lib cannot come fast enough for Belle Ramsay.

You know what she does next? She logics that shit right out. She does exactly what women do. She thinks about where the paper was last, what her husband was doing, and within an hour she has accomplished what four men working twelve hours could not do. It’s awesome, but it’s also a really weird moment, narratively, because the whole book has been trashing her and her womanly emotions and now she saves the day in a practical, smart, and efficient way. Kind of whiplash-y, honestly.

Anyway, the day is saved, the big race is here, and…if I ended this recap right here you’d know what happens. There is a legitimately great scene with all of the other jockeys, and a really cool older jockey who takes Alec under his wing, and the predictable shenanigans of one jockey being a jerk during the race. Satan wins, though, fending off Tom Volence’s Desert Storm (sired by one of the horses Volence brought back in the last book) in a stretch duel. In the winning circle, Belle Ramsey gets one last moment to being a secret hero, after her husband told her she should not have come to the race.

Mrs. Ramsay moved forward and placed her hand upon Satan’s neck. “He’s hot, Alec,” she said with great concern. “We should get him away from this crowd.”

HOORAY FOR BELLE RAMSAY.

Hey, guess who traveled to America to see the race? Abu Ja’Kub ben Ishak, that’s who, and at the very end of the book he drops the bombshell news that he’s thinking of bringing the Black back to America to race, which lets Alec twist the screws on Satan’s daddy issues one last time.

Abu had said the Black would be in the States next spring! And next spring Satan would be a three-year-old, eligible to race for the biggest stakes! It could happen that Satan would race the Black!

Satan pushed his head against him, and Alec rubbed the colt between the eyes. “Your pop is coming,” he whispered. “And he’ll be proud of you, boy. I know he will.”

Next up: we take a sideways journey to Azul Island, home of archaeologists and Spanish horses and, eventually, aliens, for The Island Stallion.

Let’s start with a summary, shall we? Everyone knows the plot of this one, but I suspect these will come more in handy as we get into the more obscure entries in the series.

So: teenager Alec Ramsay is returning from India via ship, along with a mysterious black stallion. When the ship sinks, he and the stallion swim to an abandoned island. There, they survive together and develop a bond. After they are rescued, they return to New York, where the Black catches the eye of retired jockey & racehorse trainer Henry Dailey. They begin to secretly train the Black to race, and with the help of a sports reporter, enter the Black into a match race against the two best horses in the country.

First things first: I realized halfway through this umpteenth re-read that the entire book makes perfect sense if you think of Alec as suffering from a raging and untreated case of PTSD. It doesn’t help that all the adults in his life are absolutely shitty at…well, everything. How else to explain the weird mix of naivete, monomania, suicidal tendencies, and unpredictability that basically sums up Alec’s entire character? Yet, everyone else in the book exists only to enable Alec’s least whim. Literally everyone, from Tony the racist caricature right to the owners of Cyclone and Sun Raider to his MOTHER.

That being said, I still adore this book. I am full of contradictions, I know.

Let’s start with the Black, shall we?

White lather ran from the horse’s body; his mouth was open, his teeth bared. He was a giant of a horse, glistening black – too big to be pure Arabian. His mane was like a crest, mounting, then falling low. His neck was long and slender, and arched to a small, savagely beautiful head. The head was that of the wildest of all wild creatures – a stallion born wild – and it was beautiful, savage, splendid. A stallion with a wonderful physical perfection that matched his savage, ruthless spirit.

One of the nice things about reading this on the Kindle is that I can do things like search for how many times Walter Farley uses the word “savage” in this 275 page book. The answer is 17 times, or roughly every 16 pages. Three of those instances are in this paragraph. Most of the time it’s a description of the Black’s head. I fail entirely to understand how a horse’s head can be “savagely beautiful.”

(For fun, other statistics. “Wild” gets 47 instances, “Scream” gets 32, and “stallion” gets a whopping 370, or 1.3 times per page.)

On the one hand, this description of a horse makes no sense. On the other hand, it also neatly establishes the Black as the mythic creature he is. He is not so much a horse as he is a collection of inchoate adolescent yearnings given form. He is everything that teenaged Walter Farley would have dreamed up for himself, and be honest with me: probably a lot like your childhood imaginings of the perfect horse, too.

With the days that followed, Alec’s mastery over the Black grew greater and greater. He could do almost anything with him. The savage fury of the unbroken stallion disappeared when he saw the boy. Alec rode him around the island and raced him down the beach, marveling at the giant strides and the terrific speed. Without realizing it, Alec was improving his horsemanship until he had reached the point where he was almost a part of the Black as they tore along.

In my re-read of this book, the island scenes made the least sense to me. Based on that paragraph, how long do you think Alec spent on the island? Would you be boggled if I told you nineteen days? Remember, he didn’t start riding the Black until a couple of days in. So let’s say two weeks. TWO WEEKS for Alec to tame this wild horse and become a bareback riding master.

Then they’re rescued, and can we talk about this for a second? I had totally forgotten that the ship that rescues them takes them to Rio de Janeiro first. An entirely different CONTINENT, you guys! And they send Alec’s parents a message via radio and they get a telegram back: “Thank God you’re safe. Cabling money to Rio de Janeiro. Hurry home. Love, Mother and Dad.”

Alec’s parents thought he died in a shipwreck and that is their response? Honestly, of everyone in this book, they are the most baffling. I realize that this is a YA book, of an era that had to write parents out in order for the kids to have adventures but WHAT? In fact, Alec’s poor mother is basically full-on Stepford throughout this book. Despite being their only child, they’re mildly puzzled that he returns and sort of quietly content, instead of ecstatic that he miraculously survived.

They’re also totally chill with him bringing home this totally insane horse, but it’s fine, he knocks on his neighbor’s door and they have a stall and he’ll just hang out there.

“What are you going to feed him tonight, Alec? Did you think of that?” his father asked.

“Gee, that’s right!” said Alec. “I had forgotten!”

And then they just feed him…whatever grain old Napoleon gets. Oats, or something. Which settles it: the fact that the Black did not die of colic 5 pages into this book is the real supernatural storyline.

Then Alec wakes up the next day:

He was glad his father had told him he wouldn’t have to go to school today. “One more day won’t hurt,” he had said, “and it’ll give you a chance to accustom yourself again.”

HE SPENT NINETEEN DAYS ON A DESERT ISLAND BUT AT LEAST HE GETS ONE DAY AT HOME BEFORE GOING BACK TO SCHOOL WHAT THE FUCK.

It’s a good thing Alec doesn’t go to school, though, because the Black jumps out of his pasture and lives all of our dreams, galloping loose on a golf course. This to me feels like one of the most realistic moments in the entire book. Of course he ditches his pasture. He’s a wild horse. You tear up that stupid golf turf, Black!

Thankfully, Alec gets back in time to eat the breakfast his mother has set out for him like it’s any other day and she apparently didn’t notice that he was gone? Also, his father left for work without saying goodbye? LOLLLLL. I’m telling you: all of Alec’s adults are the WORST.